A few days ago, two friends of mine shared photos of exceptionally detailed carpets and tagged me. Their designs were so intricate, they resembled photographs. While many such carpets are being made today, they rarely leave a lasting impression. The initial sense of admiration quickly fades. In the end, one simply says, “They must have put a lot of work into that,” and moves on.

About thirty or forty years ago in Isparta, there was a weaver known as “The Hoca” (I’ve forgotten his real name). You could give him a small portrait photo, and he would recreate it in a carpet—down to a single strand of hair peeking from your shirt collar. We were astonished by his craftsmanship. But I’m sure that most of those portrait carpets—perhaps even their owners—are now rolled up, mothballed, and stored away in basements or attics. They held no real artistic value. They were simply examples of fine technical work.

Not necessarily. Around 90% of traditional carpets are copies or imitations of earlier designs. Half of the remaining 10% might qualify as ordinary works of art. But within the last 5%, there are a few rare examples that stand as true masterpieces of carpet weaving—on par with the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, or Michelangelo’s David. Over the next few posts, I’ll introduce some of these remarkable works.

Let’s begin with the most iconic: The Ardabil Carpet.

Often referred to in English as the Ardabil Carpet, this remarkable piece is housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A smaller version exists at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, but the principal and most complete piece remains in London.

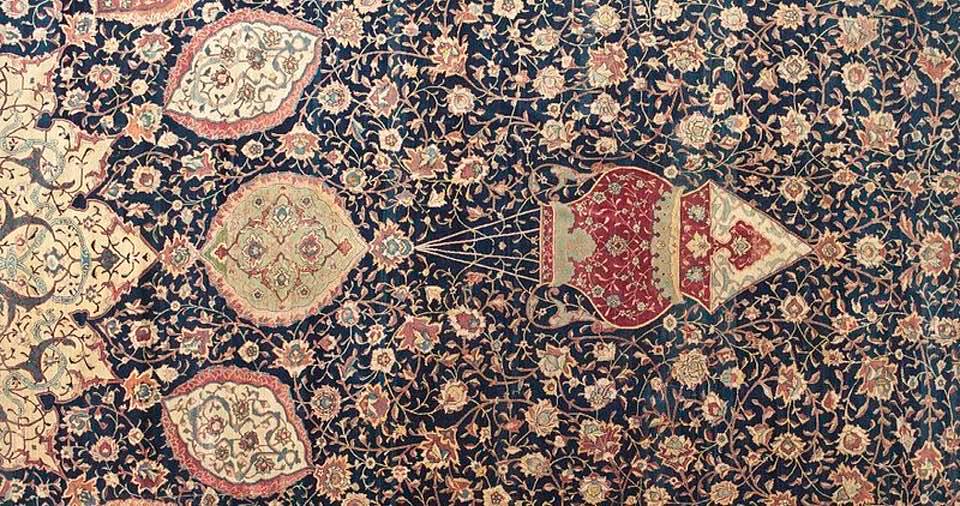

It is a very large carpet—10.51 meters long and 5.35 meters wide. Its proportions don’t follow the golden ratio, giving it a long and narrow appearance. The warp and weft are made of silk, while the pile (the surface showing the design) is wool. Natural plant-based dyes were used.

It is believed to have originated from either the Ardabil Shrine or the Ardabil Palace in northern Iran.

The Ardabil Shrine was established by the grandfather of Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid dynasty (1531–1736). The Safavids—of Turkmen origin—would go on to rule Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, parts of the Caucasus, and eastern Anatolia, becoming the Ottomans’ major rivals.

Shah Ismail himself was not only a political leader but also a celebrated poet in early Turkic literature. The Safavid dynasty, which made Shi’a Islam the official sect of Iran, emerged from a deeply spiritual and politically active Sufi order rooted in Ardabil. This carpet was most likely created by ancestors of people we now refer to—often mistakenly—as “Azeris,” who were shaped by both Persian and Turkic cultural influences.

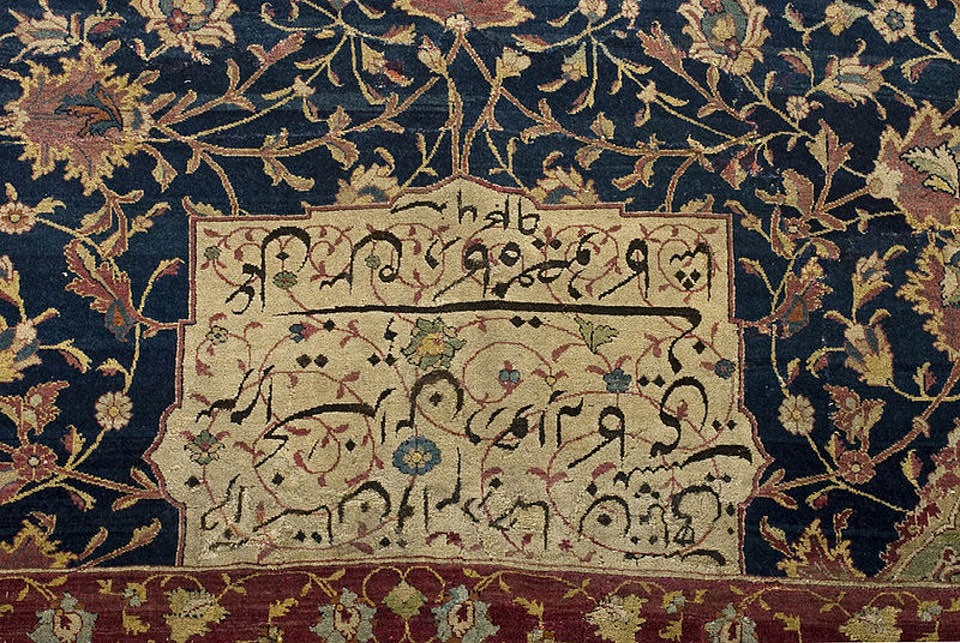

Uniquely, the artist behind the carpet is known. In one corner of the carpet, a signature is woven in: “Maqsud of Kashan”. Next to the signature is the date: AH 946, which corresponds to 1539–40 CE.

It is estimated that the carpet contains around 26 million knots. When I visited the V&A Museum, a Turkish friend joked, “If you don’t believe it, go ahead and count.”

At its center lies a large medallion, surrounded by four corner motifs. The field is filled with elegant vines and floral designs—a classic example of Tabriz style, similar to book cover designs of the same period. This layout is often interpreted as a representation of paradise.

From the central medallion extend two hanging lamps, one on each side. Interestingly, they are not the same size. Seen from above, this may appear to be a flaw. But considering the technical perfection of the piece, it is clearly intentional.

The carpet was meant to be viewed from one end, as it would be placed in a long prayer hall. From that perspective, the farther lamp would appear much smaller if both were the same size. To create a balanced visual effect, the designer made the distant lamp slightly larger. A clever optical adjustment—centuries before the invention of perspective tools or drones.

At the top of the carpet is a couplet by the Persian poet Hafez of Shiraz, followed by the artist’s signature and date:

Except for thy threshold, there is no refuge for me in this world.

Except for this door, there is nowhere for me to lay my head.

(This work was completed in the year 946 by the servant of this shrine, Maqsud of Kashan)

Originally, two identical carpets were woven, likely intended to be displayed side by side. By the time they reached England in the 19th century, both were heavily worn. It is said that fragments of the more damaged carpet were skillfully grafted onto the one we see today. Some remaining pieces from the second carpet are still held in private collections.

Sadık Uşaklıgil